Color Blindness Is Color Vision Deficiency: What It's Really Like To Live With The Condition

Jan 16, 2015 07:00 AM By Stephanie Castillo

“I’m color blind and it’s no big deal,” reads one of the several comments on BuzzFeed Blue’s recent video on color blindness. We hear the word blind and assume someone diagnosed sees zero color — but, to be clear, the condition isn’t a form of blindness at all.

Get The Facts

The condition is technically known as color vision deficiency (CVD). The American Optometric Association defines it as the inability to distinguish certain shades of color depending on the type of blindness: red/green color blindness; blue/yellow color blindness; and total color blindness (only seeing shades of gray). Red/green color blindness is the most common type, affecting 99 percent of those with the condition. The Colorado Services for Children and Youth reported 75 percent of those with red/green blindness have trouble with green perception while 24 percent have trouble with red perception.

It’s very rare for someone to be diagnosed with blue/yellow or total color blindness. Even rarer than that is achromatopsia, a type of blindness in which individuals can't see color at all.

Dr. Kirsten Albrecht, an optometrist based in Charlotte, N.C., told Medical Daily color deficiency is inherited via the X chromosome, which explains why one in 10 men experience the condition compared to 0.5 percent of women. But, Albrecht added the condition can be acquired as a result of disease, such as cataracts, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease. Unlike inherited blindness, acquired vision changes can be reversed and cured. For example, if the cataract is removed, vision will be restored.

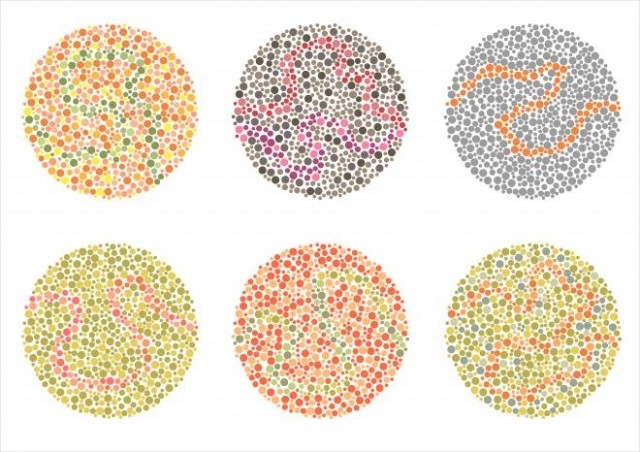

THE ISHIHARA TEST

Screening tests are available to determine CVD (except for blue/yellow blindness), though the most popular is the Ishihara test. Named after its founder Dr. Shinobu Ishihara, this test is “an odd-seeming portfolio of printed disks made up of colored dots, numbers, and squiggly lines.” Ishihara spent 50 years developing the test, and despite modern-day critiques, it’s still widely used as a quick, accurate way to screen for vision deficiency.

There are online versions of Ishihara's test (one you can take here), too. When we asked Albrecht if these tests were as effective as seeing an optometrist, she said they worked more to get patients into the doctor's office rather than diagnose their condition.

“If you want to get a true sense of a deficiency, take the time to visit a doctor,” she said. “You can’t rely on an Internet test to give the basis of the specific type [of blindness].”

Andrew Heder, 26, who was featured in BuzzFeed's video, told Medical Daily he learned he was color blind after medical professionals visited to conduct a series of health-related tests in elementary school — tests Heder was otherwise acing. But when he couldn't discern the shapes and squiggles on the “cards with the dots on them,” he was confused.

“I remember doing it in my teacher’s office and thinking, ‘What is going on?’ Everything was normal up until then,” Heder said. At the time, he was 7 or 8 years old, so he can’t remember exactly who told him what that meant, but he does know it wasn’t a school official or nurse. He believes his mom broke the news he was "slightly color blind" after disagreeing on the color of her ’94 forest green Passat; he thought it was black.

When Heder heard his mom say the words “color blind,” he rejected it out of hand. He could see color — he wasn’t blind. But in fact he could not see red/green color. And today, the problems that stem from his condition are very minor. It doesn’t affect him much at all, actually.

“I can see red and green; those are very brilliant and different colors,” he said. “It’s when the spectrum fades toward purple [I have trouble].”

COPING WITHOUT COLOR

Since there’s no cure for inherited CVD, those diagnosed with the condition focus on coping strategies and cues. An example Albrecht focuses on pertains to traffic light signals. Someone who is color blind will learn how to utilize color filters, and which colors are designated in the top, middle, and bottom of the light, so they’re able to better distinguish between them. Patients can also opt for corrective contact lenses.

In 2012, The Wall Street Journal reported a genetic test was developed to identify the exact type of color blindness, as well as customizable tools patients can utilize in their daily life.

Today, there are apps, awareness campaigns, and most recently, sunglasses. The Huffington Post reported EnChroma, a California-based company, has created kid- and sports-friendly color blindness correcting glasses — an item Heder might have wished existed before now. He told BuzzFeed his condition made it hard to tell apart his soccer team from the opposing team, so he accidentally passed them the ball... twice.

COLOR BLINDNESS MYTHS, DEBUNKED

Heder read the comments on BuzzFeed’s video and was surprised by how interested in the topic people were. More importantly, he saw how equally annoyed those with color blindness (or those with friends with color blindness) were by his least favorite question, “What color is this?”

“I think the title of [the condition] is misleading, because blindness is a pretty black and white term,” Heder said.

Albrecht would agree.

“The biggest misconception is folks don’t see color at all — that’s not the case for the vast majority,” Albrecht echoed. “It’s just a difference in how intensely they see color. [In my practice,] we make sure to reassure parents it’s not something that’s debilitating at all. It’s just something we need to teach them to cope with.”

And that’s if a patient’s color blindness is even, like BuzzFeed commenters described, a big deal. While Heder doesn't view his condition as such, he's still prone to color mistakes.

“There are times if I’ve made a mistake with the color, and the person I'm with doesn't know [about my condition], I just don’t say anything,” he said. “People react pretty strongly when I say I’m red/green color blind. They’ll be like, 'Oh, no way,' implying it’s hard for me. But I don’t want it to be seen as deficient.”

I asked Heder what, if given the chance, he would rename his condition to. Blindness is misleading, deficient seems too negative, so what would be more accurate? He settled on Color Spectrum Differentiation in order to emphasize the problem is with color, not necessarily vision.

He said, “I like to think I could still be an astronaut one day if I wanted to.”